- Home

Page 4

Page 4

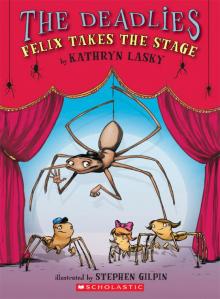

Felix Takes the Stage

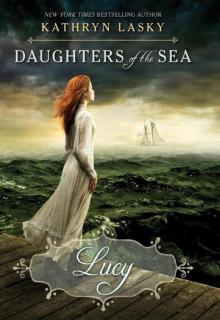

Felix Takes the Stage Lucy

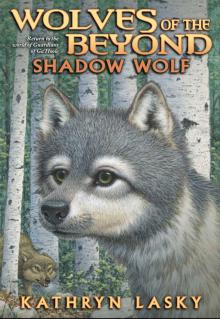

Lucy Lone Wolf

Lone Wolf Broken Song

Broken Song The Shattering

The Shattering The Crossing

The Crossing May

May Chasing Orion

Chasing Orion Star Rise

Star Rise The River of Wind

The River of Wind More Than Magic

More Than Magic Born to Rule

Born to Rule The Hatchling

The Hatchling The Rescue

The Rescue Marie Antoinette: Princess of Versailles, Austria - France, 1769

Marie Antoinette: Princess of Versailles, Austria - France, 1769 The War of the Ember

The War of the Ember Spiders on the Case

Spiders on the Case To Be a King

To Be a King The Last Girls of Pompeii

The Last Girls of Pompeii The Outcast

The Outcast Exile

Exile Night Witches

Night Witches Spirit Wolf

Spirit Wolf The Quest of the Cubs

The Quest of the Cubs Frost Wolf

Frost Wolf The Keepers of the Keys

The Keepers of the Keys The Extra

The Extra Blood Secret

Blood Secret Watch Wolf

Watch Wolf Blazing West, the Journal of Augustus Pelletier, the Lewis and Clark Expedition

Blazing West, the Journal of Augustus Pelletier, the Lewis and Clark Expedition The Capture

The Capture The Burning

The Burning The Journey

The Journey Unicorns? Get Real!

Unicorns? Get Real! The Escape

The Escape Star Wolf

Star Wolf Ashes

Ashes Wild Blood

Wild Blood Tangled in Time 2

Tangled in Time 2 The Siege

The Siege Hannah

Hannah Elizabeth

Elizabeth A Journey to the New World

A Journey to the New World Christmas After All

Christmas After All Mary Queen of Scots

Mary Queen of Scots